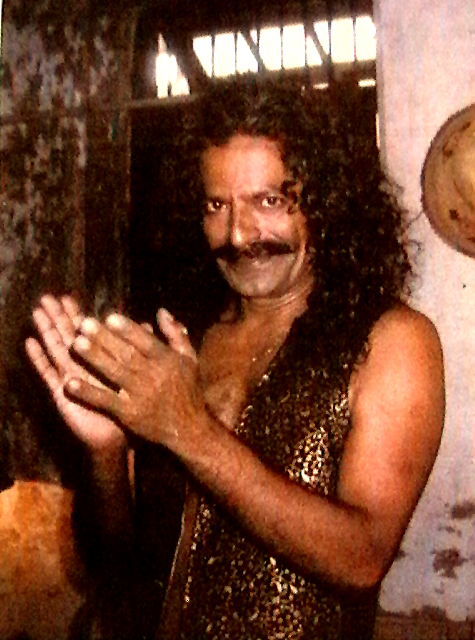

Mumbiram’s artistic journey in India proceeded on an entirely independent path, away from the haloed portals of academia, away from museums and art galleries, away from auction houses and exhibitions. It was a deliberate and intelligent choice. It was only after manifesting the glorious workings of his own chosen path that he commented on the contemporary art scene:

“The domain of contemporary art is laid barren by meaningless abstraction, compulsive self-inflicted distortions and ridiculous installations. Art has lost its credibility. It is prima-facie irrelevant. Art lovers are becoming cynical about the intellectual pseudo-spiritual props that must hold up all contemporary art. We are all becoming cynical that auction houses have become the arbiters of what is good taste and what is beautiful. There exists no theory of aesthetics that would provide us with reasonable criteria to gauge the relative merits of works of art. All art-criticism has become subservient to the market-place and entirely impotent. Art has lost its romance.” (Mumbiram)

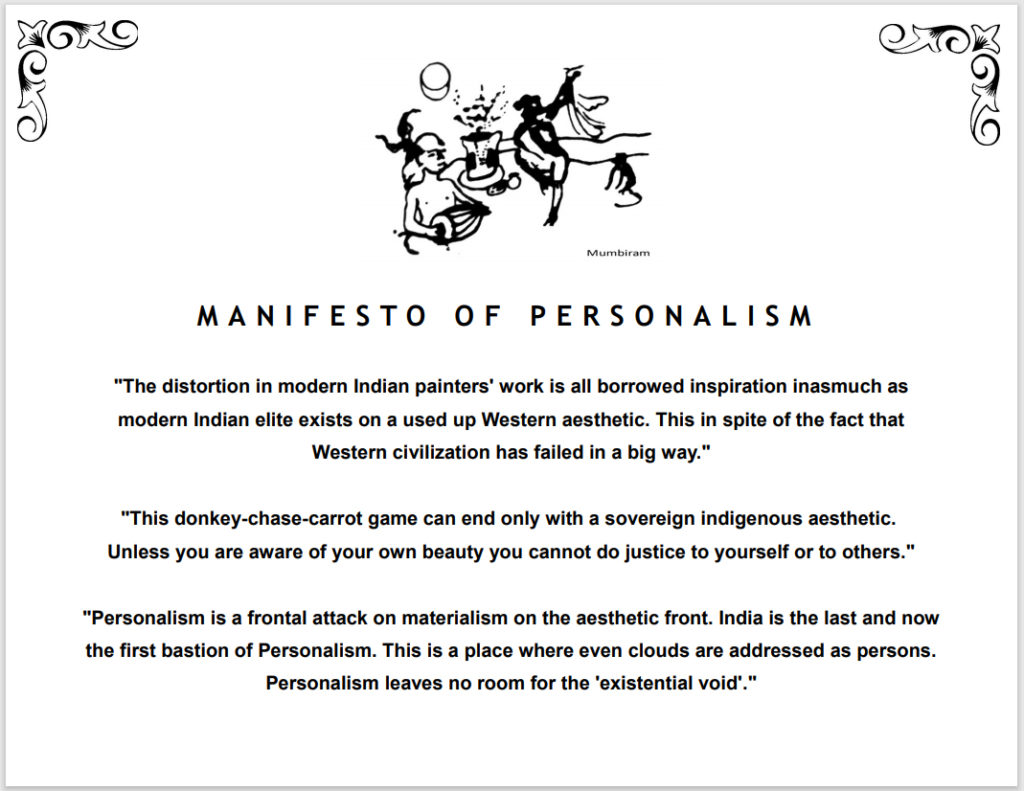

Mumbiram sees the most fundamental dichotomy of our age as Personalism versus Impersonalism. He chooses Personalism, as he squarely asserts that it is the individuals that comprise the organisation that are greater than the structure of the organisation. According to the tenets of Personalism, an Impersonal paradigm of divinity gives rise to the existential void and absence of values. Love of impersonal objects, in preference to love of individuals, gives rise to materialism. Impersonalism in art is epitomised in abstract art.

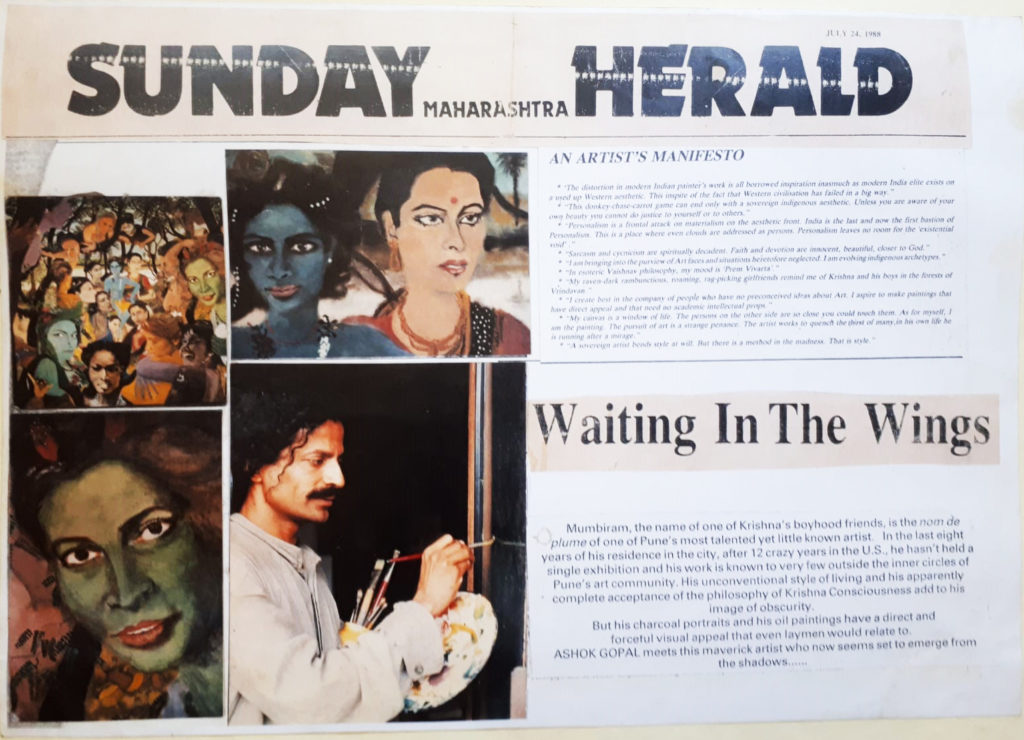

In the article “Waiting in the Wings” by author and journalist Ashok Gopal, where Mumbiram’s manifesto of personalism first appeared, the author describes Mumbiram’s views on the art establishment:

“Mumbiram’s work shows people to the exclusion of almost everything else. He has no interest in the environment in which his subjects live and he has scant respect for the increasing number of contemporary Indian artists who grossly contort the human figure to make a cynical or sarcastic comment about the world around us. ‘Such contortion, he says, may have been justifiable in the West which faced the horror of Fascism, genocide and World Wars, but in India a similar expression of “anguish” is misplaced and mindlessly imitative. In any case, depiction of mental or physical torture is of no use to either the artist or the viewer unless there is a hint of a way to transcend it’.”Modern art, he says, is predominantly conceptual. This is its power as well as limitation. It’s like a joke. The first time you say it, it can sound great but on repetition it progressively loses impact. Likewise, the artist who first exhibited blank canvasses in a gallery made a strong point and deserved credit; but anyone who tries to repeat the “trick” can only deceive his viewers through elaborately presented jargon.

These are not views the art establishment will welcome and they can possibly come only from an artist who would be happy to be considered a classicist in the tradition of Leonardo da Vinci, the Renaissance genius with whom he shares at least one quality: a striking recurrence of certain facial features over a large body of work.”

Genesis of the Rasa Renaissance Mood

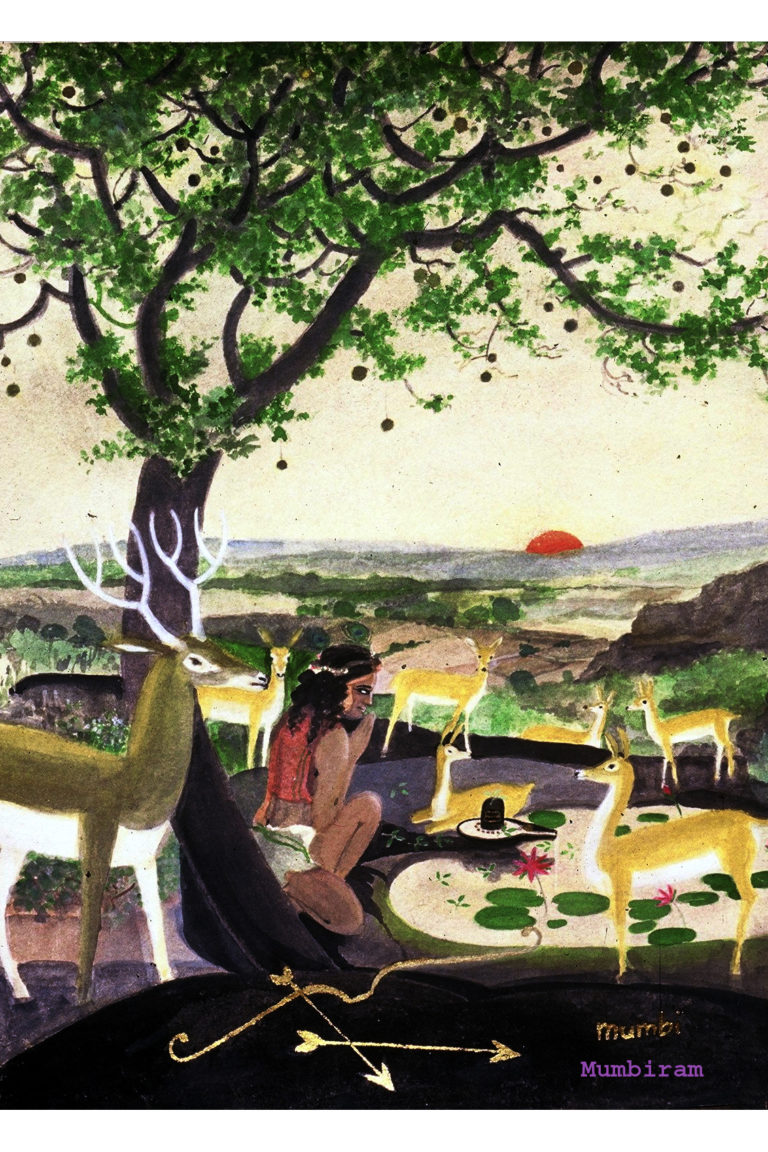

Mumbiram had become fascinated and enamored by a verse from the Tenth Canto of Shrimad Bhagavatam. This is from the celebrated Rasapanchadhyayi selection consisting of the Venu Geet, Gopi Geet, Yugal Geet, Bhramar Geet and the Uddhav Geet. In the Venu Geet there is the verse that tells about the extraordinary and astounding amorous attraction the wild forest dwelling Pulindya women felt towards Krishna. Great Krishna lovers have known that the Pulindya men and women inhabited caves in Vraja. Some Pulindis were friends with Krishna and some were helping Shrimati Radhika. They would offer forest products to the Divine Couple. That would include even bamboo sticks to fashion flutes out of. Some Vallabh Sampradaya devotees know that the Pulindis very often host Krishna in the caves of Govardhan Hill. Some Gaudiya acharyas have surmised that the wives of the Yadnik Brahmins had never seen Krishna before. They heard about his Supremely attractive personality from the Pulindis that they met in the markets in Mathura !

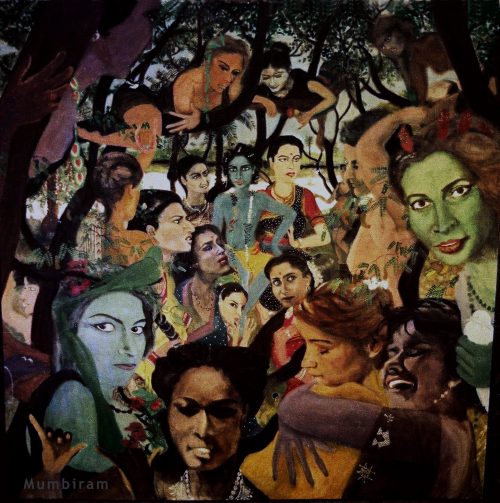

Mumbiram’s great masterpiece “Forest Women visit Krishna and the Gopis” happened in several different versions, beginning with the first as a mural in Seattle in 1979. The one that he made while living in his legendary Mandai Atelier happened in 1984-85. It is considered to be the flagship of the Rasa Renaissance Movement. Ashok Gopal has printed an image of it in his long article of 1988: “Waiting in the Wings”. A detail of that masterpiece is printed in the “Sunday Observer” article of 1988. Mumbiram’s “Book Readers” Catalog published by Distant Drummer gives a good introduction to Rasa Theory as the basis of Mumbiram’s Rasa Renaissance.

Both these articles about Mumbiram written in 1988 have chosen the very colourful and exuberant “Forest Women visit Krishna and the Gopis” masterpiece besides other coloured masterpieces.

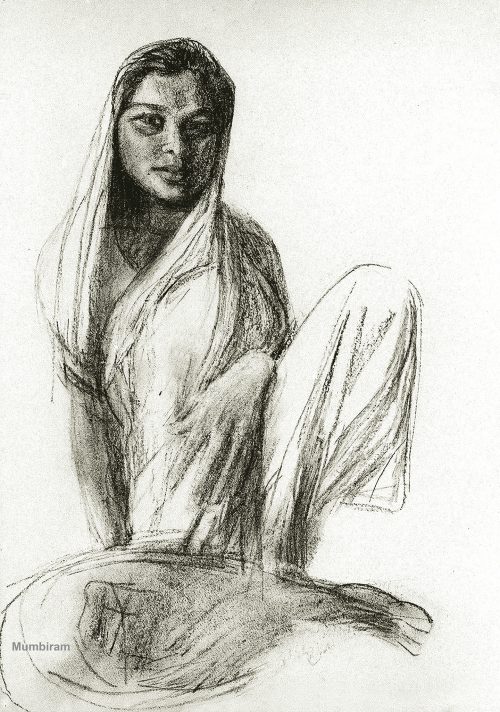

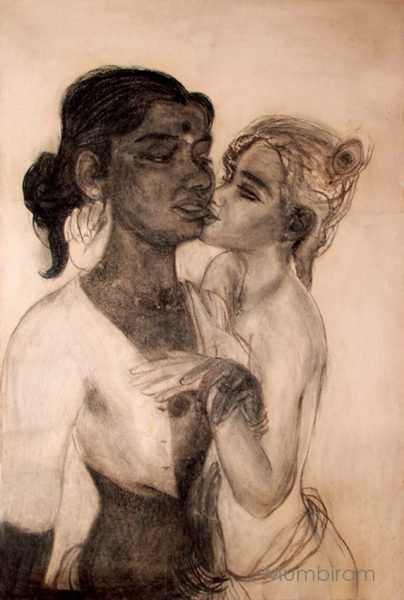

However neither has escaped Mumbiram’s very own unique genre of rapidly executed charcoal portraits and Leelas in the Prema Vivarta mood. Indeed Mumbiram’s art was attracting the viewer’s attention without any intellectual or psychological props. None of these three charcoal masterpieces has even a title mentioned in the articles.

Ashok Gopal has chosen Mumbiram’s iconic portrait “Yamuna” which he had made some time before 1985 and was soon after spontaneously acquired by a young German enthusiast from Berlin named Swami Viren on his very first visit to Mumbiram’s atelier. “Yamuna” has already attained an iconic status as a Mumbiram charcoal portrait of austere everlasting charm.

Most of Mumbiram’s masterpieces have a post of ‘Rasa Appreciation’ about them. This is a unique feature of Rasa Art. The quality of emotional fulfillment that a work of art brings to the artist, his muses and his admirers is the ultimate goal of that noble endeavour.

When you read the Rasa Appreciation of “Yamuna” you realize how Mumbiram had a personlist outlook on every facet of life and art.

The Sunday Observer published from Mumbai had chosen two charcoals depicting two young friends frolicking in good-hearted bold but innocent horseplay. These have been obviously inspired by the ‘Dalgi Leela’ which we have presented in another post.

Early example of Leela in the Prema Vivarta Mood

Mumbiram has already mentioned the Prema Vivarta mood of relation with the Supreme in this manifest. For a devotee in the Prema Vivarta mood everything in the material world is reminding him of something in Goloka, the eternal original abode of all living entities. He is having a continuous deja vu like experience of relation with Krishna and his loving associates in Goloka Vrindavan. Mumbiram has said that this is likely what is at the root of his attraction to the rag-pickers and phasepardhi bird catchers and roaming buguwalis.

On hindsight we can say that it was not an accident that the reviewer of Sunday Observer was unknowingly attracted to this pair of rapidly executed charcoals depicting lively interaction between friends that share unmitigated trust and love. Granted, in the world of contemporary art such loving lively interaction between real-life ‘ordinary’ people stands out as rare exception. But also on hindsight we know that such depictions in Mumbiram’s iconic charcoal masterpieces are attractive in a mysterious inexplicable manner precisely because they subliminally remind the viewer of some nectarean Leela in the Vrindavan Pastimes of the adolescent Krishna along the bank of the Yamuna or in the vales of the Govardhan Mountain.

Artist Mumbiram himself was inspired to depict such a Leela for the same identical reason. This is the essence of the Prema Vivarta mood.

The ‘Dalgi Leela’ that we have mentioned is a vivid and wonderful example that illustrates Mumbiram’s assertion “My raven-dark rambunctious, roaming, rag-picking girlfriends remind me of Krishna and his boys in the forests of Vrindavan.” that is mentioned in the Manifesto of Personalism. Indeed Mumbiram’s manifesto is not just dry philosophy but a vivid expression of personal experiences that show how rasa art is an outcome of the intertwining of emotions of all participants of that noble endeavour.

Dalgi Foto – Post

Indeed it is only by a stroke of good luck that an episode that took place in the early pre-dawn hours in the lives of rag-picking girls from the slums on the outskirts of Pune as they went out on their daily foraging for odds and ends lying on the roadside was captured by a Rasik Artist who could only see Krishna and his friends wandering in the forests of Vrindavan.