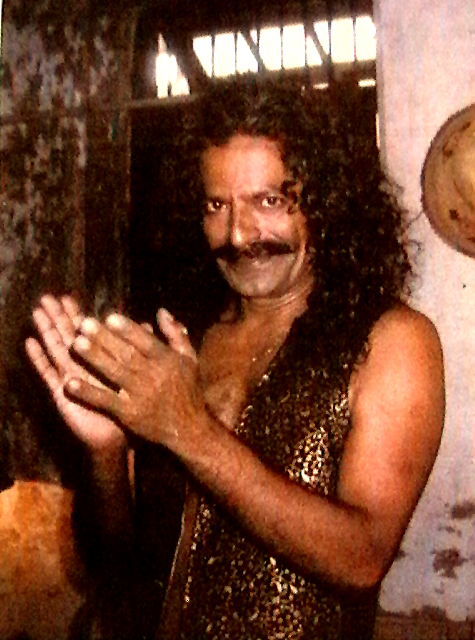

“Practice of Personalist Art” (1985, Pune Sakal) reveals a man who stood up to the U. S. State Department and insisted that he be deported to India for purely aesthetic reasons.

Mumbiram’s writing is full of energy. It takes us as nonchalantly through the corridors of power in Washington as it takes on a tour of the beauty-spots of Pune’s downtown where he established his studio in a run-down house. His writing has this enlivening quality of equanimity vis a vis cultures. For Mumbiram it was just natural to follow his attraction to the tribals and ‘lowest’ castes of India who became his friends and muses. Mumbiram’s uniquely independent position as a Personalist Artist and his soulful findings in the “fields of beauty” make him an acutely sensitive commentator on profound issues.

“After 12 years stay in America I came to India in 1979. I had considered my stay in America as a ‘tapa’, a period of penances and austerities. I had not come back with a bundle of money like everybody else. Yet I considered myself rich with the fruits of my ‘tapa’. I had gone to America to become a captain of the ‘Third Wave’ of modern technology and I had come back as a lonely cavalier in the fields of beauty. My personal gain was even greater. It was in America that I found Krishna, his teachings in Bhagavad Gita. Compared to this treasure I considered any other gain of less value.”

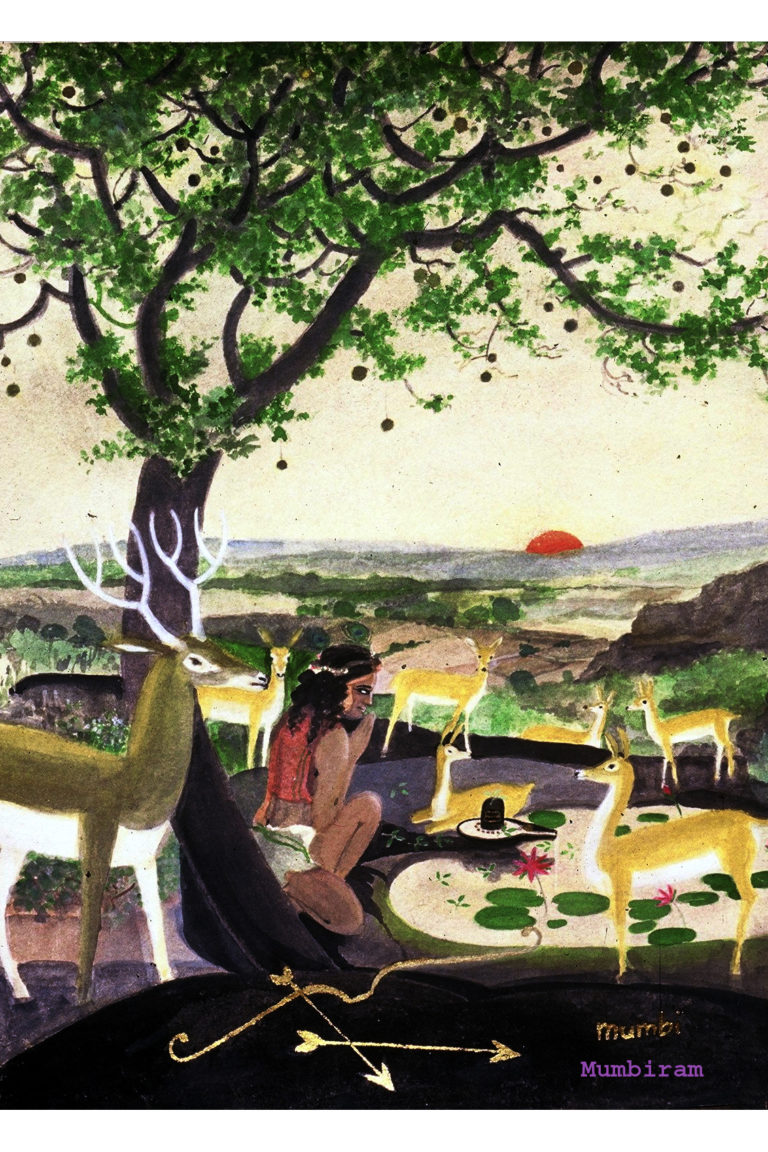

“My grandfather the artist was dead. So was my father’s mother to whom I was dear. There was an uncle of mine who was a literary critic and who was the first discoverer of my artistic talent when I was still a child. He had also passed away. I prayed for all these dear departed souls and went away to the hills of Dahanu, 100 miles north of Bombay and lived there with the tribal Warlis for a long time.”

Mumbiram’s approach is thought provoking. He does not go to the Adivasis or to the bird-catchers or to the rag-pickers as a do-gooder. He sees his association with them as a learning and creative environment for his own aesthetic search. This is distinctly different from the attitude of the social worker who is insensitive to the grace and the ambiance of the natural people and who in the long run may only bring a cheerless ruin to their happy lives as a price of ‘civilization’.

Mumbiram’s approach is also different from that of the culture vultures who hunt for Adivasi artefacts as objects of upper middle class interior decoration. According to Mumbiram art embodies the impetus of evolution. Art that sets its goal on anything less is inferior.

“I enjoyed painting most in a place where there are no preconceived expectations out of an artist. My Warli young friends – both men and women – tremendously enjoyed my pictures of the American Marriage System. Nowadays everybody raves about the stick stones style of Warli pictures. As for me, I would never expect my Warli friends to continue in that style. Just as an artist can become limited by its quirks. The pleasure of art is precisely in finding new paths when modes of expression become hackneyed. Art at its best is the motivation behind evolution. Living with the Warli tribals I could do ink-and-brush renderings in such a minimalist and ethereal style as I would never have been able to do anywhere else in whole world. With them I could paint the innocence of love that goes beyond the pail of morality.”

Mumbiram is passionately in love with cultures in the lofty manner of a Whitman or a Thoreau. “Confluences of Art Movements are pilgrimage places of Culture” (Mumbiram).

Mumbiram sees aesthetic excellence as the force that can unite our world that stands divided by Ethnic Chauvinism. In his writing we get the refreshing glimpse of an ethos that transcends cultures by acknowledging them rather than avoiding them. Commenting on Pune’s culture of nascent industrialization Mumbiram alludes to Oliver Goldsmith and the Bhagvat Purana in the same breath. In Mumbiram’s writing we come across the finest outcome of the East-West encounter.

What truly distinguishes Mumbiram as the prime proponent of Personalism is the lucidity of his writing even about profound issues.

Mumbiram sees the most fundamental dichotomy of our age as Personalism vs. Impersonalism. He chooses personalism as he squarely asserts that it is the individuals that comprise the organization that are greater than the structure of the organization.

“In art I do not acknowledge the abstract vs. realist duality. Omitting the detail that is redundant for expression is abstraction. This is natural abstraction. Knowingly or unknowingly every artist is doing it. On the other hand, creation of meaning from juxtaposition of symbols is synthetic abstraction. Our Warli art is of this latter type. Both these modes are used in drama as a matter of course. I feel especially close to the dramatic art.”

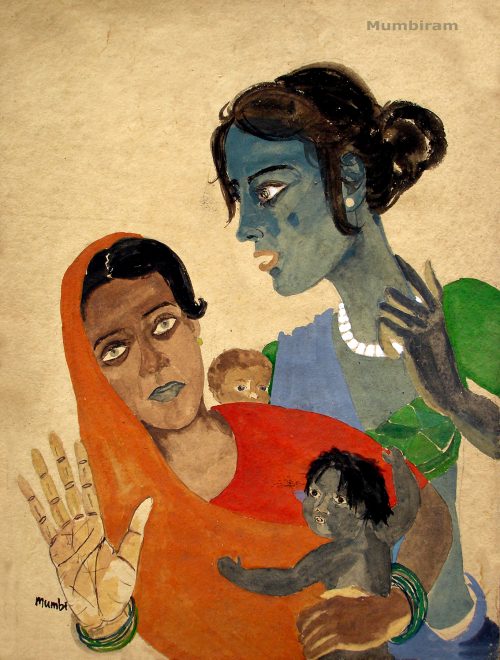

Mumbiram is fascinated by the dark beauty of India, yet, fiercely independent that he is, his subjects, his rendering, his titles, his perspective are always full of pleasant surprises and avoid the obvious.

In Mumbiram we have an acutely sensitive commentator of a socio-political milieu. In the light of his personalist aesthetique Mumbiram finds it deplorable that marriages in India are based on data-matching rather than on mind-meeting.

“In general in India men and women live segregated existences. Sometimes the divide is seen to be so great that even life time partnerships are fixed by advertisements in the newspapers, from matchmaker’s lists and now even from computers. Cast, economic status, education and other social and statistical details is what characterizes men and women. I find it very incongruous and unagreeable to my ‘personalist aesthetic‘. An open, honest and forthright friendship between men and women in India is a very rare thing. The hide and seek that they have to play is such a waste. I find it very tyrannical.”